Conversations.

Most of my day is spent talking to people, considering their unique situations and deploying the strategies we’ve worked hard to understand into their lives.

Over the last week, three of these chats stood out. Each started with a question:

Question #1: “Adam, I think we should take more risk. What do you think?”

Before I get to my response, here’s the overview of this client:

Mid 80s.

Healthy.

$3.5m Portfolio with Harding Wealth — allocation is already aggressive.

$5m Net Worth.

No debt and doesn’t need much from his portfolio.

His definition of “take more risk” was mostly about trying to find some individual stocks in pursuit of a big payout.

This is an interesting situation.

On one hand, the majority of his wealth isn’t needed, and the less you need funds, the more risk you can take (Think of the $10 you spend on the lottery every once in a while. When you end up losing 100% of your lottery ‘investment’ it’s okay because you didn’t need that money.)

On the other hand, at some point the losses feel worse than gains (Prospect Theory, Kahnehman & Tversky).

So, here’s what I asked him:

”Let’s pretend for a minute that your portfolio instead of $3.5m is $5m. Would you feel any different? Would you do anything differently?”

I knew he’d say no. But if he had said yes, I would have laid out the math for why $3.5m is likely enough to do what he wants to do.

So then I followed up with:

”Okay, so a jump from $3.5m to $5m doesn’t change things; how about a reduction from $3.5m down to $2m?”

His response indicated what I already knew: the idea of a $1.5m loss hurts way more than the benefit of a $1.5m gain.

There is no blanket response to give to every investor when asked “Should I take more (or less) risk?” — everything is circumstantial. That’s what we’re here for.

Question #2: ““My account only made 8% last year! Why?”

A few times a week I’ll have a conversation with someone who isn’t a client but needs another opinion about their finances. They tell me about their life, their money, what things look like today and what they want things to look like in the future. Then I tell them what I think. This is the first step in deciding if it’s a good potential fit to work together.

Last week I spoke with someone who was looking into their 2025 investment returns with her current advisor and had some questions. In particular she asked “how did I only make 8%?”

This is a fair question. After all, the S&P 500 was up 17.9% last year.

I asked her about her life and her money.

55 years old.

Married.

Working.

Comfortable with volatility.

No reasonable need to draw from her portfolio until age 65 at the earliest.

When we see a portfolio underperform the stock market this dramatically (8% vs. 17.9%), the typical culprit is simply that the portfolio wasn’t entirely invested in stocks. This explained part of it. She checked her allocation and it was about 70% stocks, 30% bonds.

When she told me this, it meant one of two things:

1) The advisor landed on this allocation because that’s how they treat every 55 year old (this is what 401k plans and target date funds tend to do — make an assumption about your needs based solely on your age, not your circumstances).

2) The advisor believes in making tactical guesses about the short term market environment and, in this case, guessed wrong by establishing a 30% investment into something designed to prevent losses in a stock market correction. And when that correction didn’t happen, it caused the portfolio to lag.

If someone has 10 years to remain invested, we generally believe they can take on stock market risk. Those 10 years may be a bumpy ride but we think those bumps are a reasonable price to pay for the potential upside.

And, look, there are very good reasons for a portfolio to lag the stock market: you don’t have the stomach to have all of your funds in the market, your needs don’t require you to take big risks, or you’re allocated in a way that’s designed to have a smoother glide path. Just make sure those reasons make sense to you.

(One more side note about this investor’s underperformance: the 70% that was in stocks was largely allocated to individual companies and not broadly diversified funds. That’s a topic for another blog.).

Question #3: “What do you think about trading?”

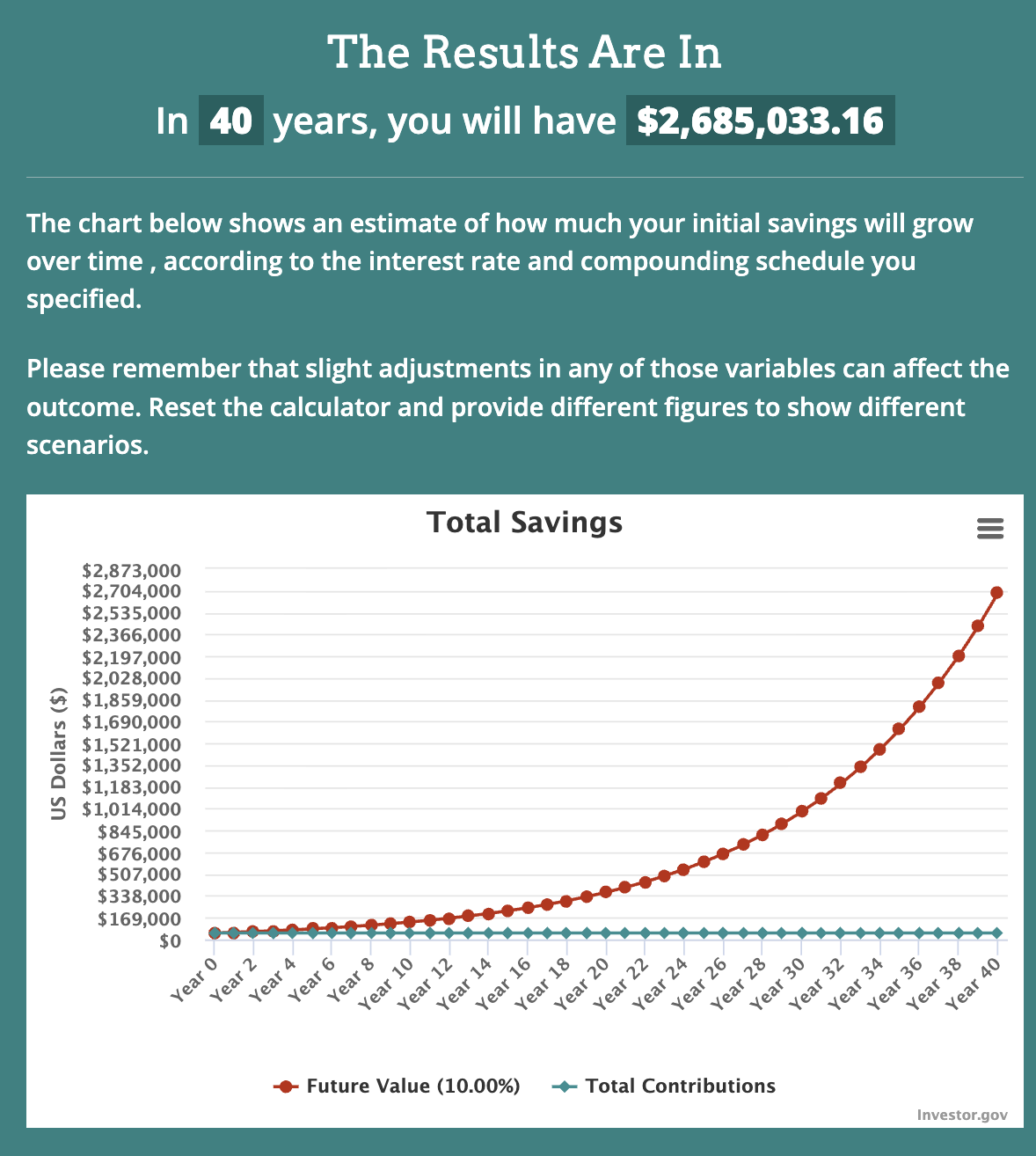

10% annual returns for 40 years would change your life.

Here’s what $50,000 turns into (hypothetically) with no additions or subtractions.

Not an actual investment. For educational purposes only.

$50k turned into nearly $2.7m is crazy. Everyone would sign up for that.

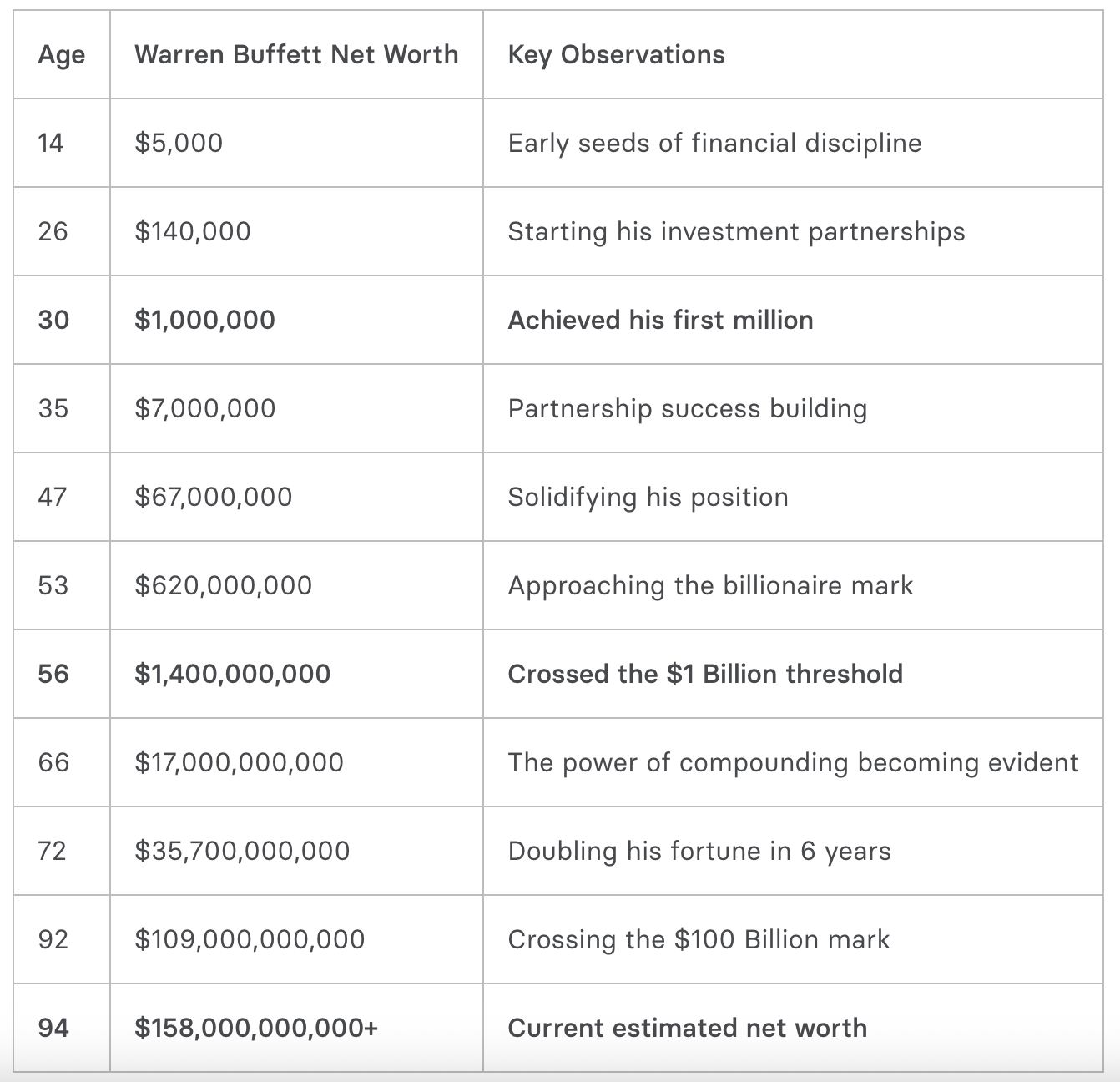

But look back at that chart above and how absolutely boring it is on the left side of the X axis. This isn’t unique to a hypothetical portfolio, even Warren Buffett accumulated roughly 99% of his wealth after age 50.

See for yourself:

Crazy to see this effect, right?

But let’s go back to the 10% example and think about a new investor just starting out with a $1,000 investment.

How absolutely boring is it to get a 10% rate of return your first year to end with $1,100?

Especially when that same young investor is being bombarded with ads from FanDuel and DraftKings, while their social media feeds are filled with pretenders in rented Lamborghinis offering “blueprints” for huge profits trading the markets—usually forex, crypto, or options. So when a 27-year-old family friend asked me the other day, “What do you think about day trading?” I knew exactly where he was coming from. He confirmed that his friends had been trading and telling him about their gains, and that he’d seen courses offered online.

I explained why these courses are bullshit—mainly, why would someone sell you alpha for a few thousand dollars when a hedge fund would gladly pay millions for the same strategy? I also explained that his friends were probably underreporting their losses (only about 1% of day traders and roughly 3% of sports bettors actually make money). But the main thing I tried to understand was why. Why risk significant—or even total—losses in exchange for the possibility of a higher payout?

Young men in particular are increasingly drawn to these high-risk, low-odds pursuits as a way to skip the line on wealth accumulation. And frankly, I get it. Saving a little at a time while the cost of everything around us has ballooned makes getting ahead feel impossible. But the old playbook still works, and it’s never been easier or cheaper to implement with modern investing platforms. Unfortunately, this playbook doesn’t go viral the way a guy touting profits from the deck of a rented yacht does—which is why we spend a fair amount of time working with the adult children of our clients.

I encouraged my friend to stick with a prudent plan, focus on his career and family, and treat his friends’ success stories with a healthy dose of skepticism.

And if the people in your life need a voice to help counterbalance the noise, steer them our direction and we’ll try to be that.

That’s all for today. Happy New Year.

Adam Harding

Schedule a Chat

For informational purposes only. Not investment advice.